Why an AI can’t automate protocols from a paper

... and how it can help

This is a question we get a fair bit. A common job for a scientist is reading a method documented in a paper, or a protocol in their ELN, and trying to get it to run for real.

With the advent of LLMs, we’ve had questions from folks wondering whether we could take these methods and translate them directly to robots to run. To cut out the tedious manual translation and wet lab validation that scientists must do during development, and get to an automated system that at least performs the correct actions, even if some of the specifics of the science need ironing out.

We’re not there yet, but thinking through why we aren’t can actually tell us a lot about what makes automating science hard, and more broadly, why reproducing science is a struggle. Let’s dig into it.

The moving target of protocol detail

A problem that every scientist is familiar with. Protocols are often insufficiently detailed to be run in precisely the way that was intended. This sounds like a simple problem with a simple solution – scientists should just include more detail when they document their experiments.

The trouble is that for manual science the ‘correct’ amount of detail is actually a moving target. Tell an experienced cell biologist to ‘Gently wash the HEK cells with PBS’, and that may well be all they need to know. They’ve handled mammalian cells before, so including more detail than this would seem redundant.

A molecular biologist who’s only worked with E. coli might need to know how much buffer, whether to gently aspirate, and how long to leave the buffer before removing it. A fresh graduate would need even more – perhaps a gentle reminder of their sterile technique!

And what does the robot need to know? Well, everything. It has no understanding of the science – it’s programmed purely mechanistically. It doesn’t understand how to handle mammalian cells, it doesn’t even understand the concept of gently. It needs a step-by-step guide with each and every variable spelled out.

When a scientist asks an automation engineer to automate their protocol, part of the job is extracting all of these details. Not just ‘which buffer do I use’, but also ‘what does gently really mean’? This requires conversations with the scientist – in order to bring together the scientist’s understanding of their process, with the engineer’s mechanistic knowledge of the automated system.

An AI can’t directly automate a paper for the same reason that scientists struggle to reproduce them – all the details compressed into “Gently wash the HEK cells” have to be unpacked. Even experts in cell biology will bring different context and assumptions to unpacking those details. An AI will do the same. It can take educated guesses at these specifics, but without an interface with the scientist, it’s very unlikely to be correct.

Onto another problem…

What can your equipment actually do?

Automated labs usually do not contain all of the equipment and capabilities of a manual lab. Without access to the same equipment, workflows need to be adapted to this equipment.

This happens in manual reproduction too – the reproducing lab often has different equipment than what was used in the original experiment. Changes range from simple tweaks, like matching the G-force on centrifuges with different rotors, all the way to developing an entirely different assay to overcome a missing channel on a plate reader.

When automating, adapting the protocol to the equipment is a huge part of the job. Moving from tubes to plates, switching from spin columns to mag-beads – these are concrete changes to protocols that scientists often wouldn’t consider when manually replicating someone else’s experiment.

To an engineer, some of these incompatibilities are immediately clear when reviewing their scientist’s protocol. Our workcell doesn’t have a centrifuge! Some are less obvious, and will only become clear once all of those hidden details are unpacked.

For an AI, making these adaptations is challenging. Context is key – the context of what equipment is present in the lab, and the constraints of that equipment. And even more tricky, the scientific (and economic!) context – a deep understanding of why protocols have been designed the way that they have been – does the scientist keep their reagent in a 1.5 ml tube because that’s how it was sent to them, or because it costs £1000 for 300 μl? If it’s the latter, the automator probably shouldn’t just dump that reagent into a single well reservoir.

Can an AI do anything to help?

An overriding theme here is translation – bridging the gap between scientific intent, and the concrete actions, functionality and constraints of each automated system.

Let’s start with unpacking that scientific intent. While an AI can’t know all of the detailed intention of the scientist, it can spell out the necessary details for automation and take an educated guess at what they might be. Then it can hand the reigns back over to the scientist to ensure the protocol matches their expectations.

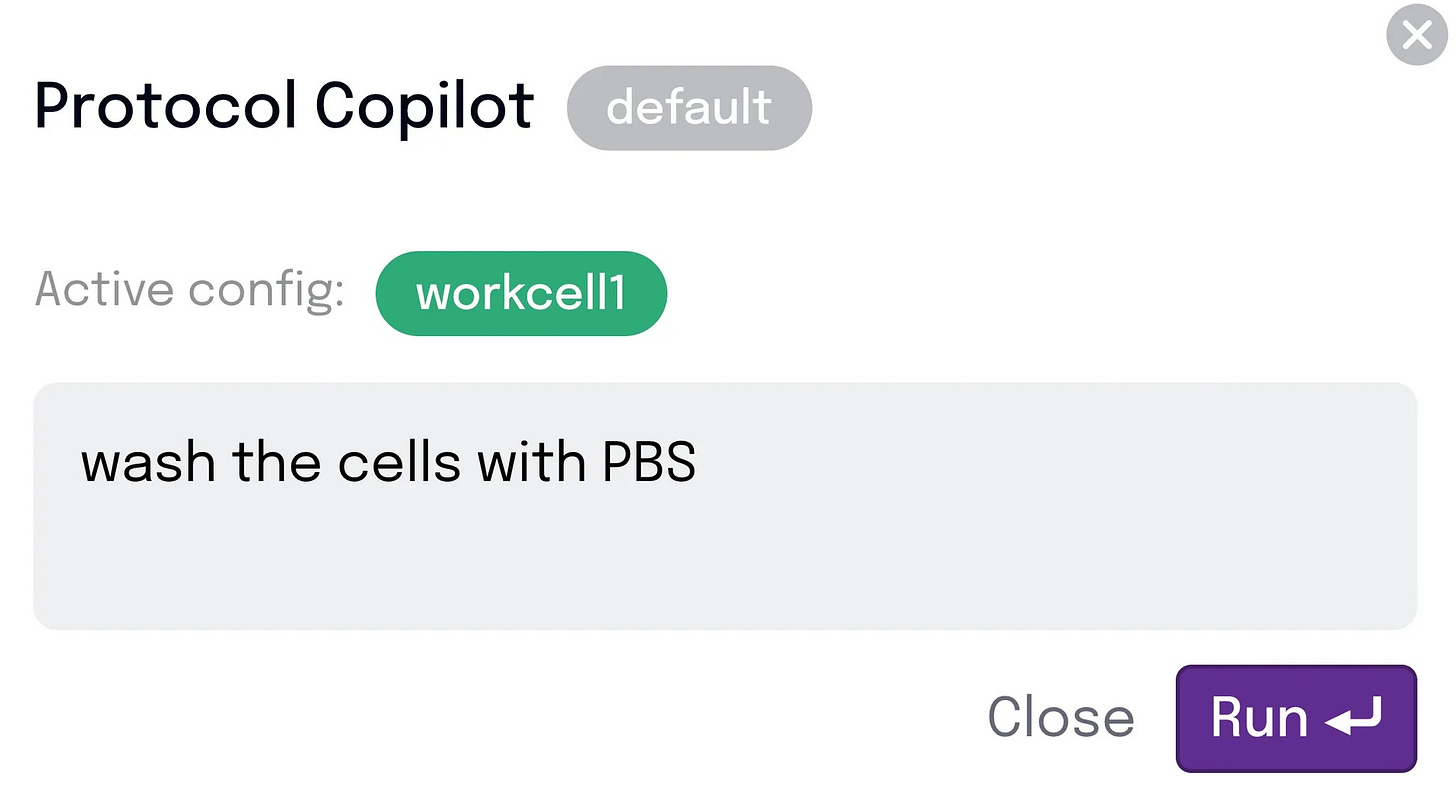

Let me show you within the context of the example I mentioned above – washing HEK cells. The scientist starts with an instruction that makes sense to them – “Wash the HEK cells with PBS”.

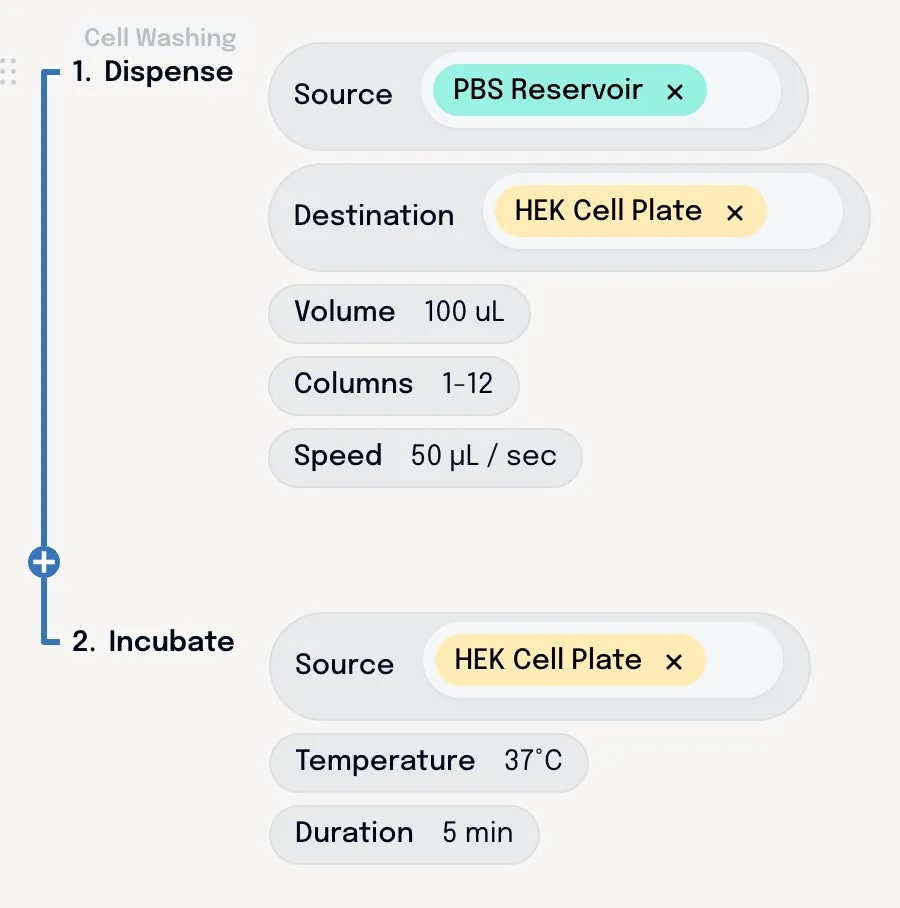

The AI unspools this into mechanistic steps and parameters – based on its understanding of washing HEK cells. With all the details laid bare, our scientist can make adjustments from there to ensure it aligns with what they actually want to do.

And what about the constraints of the system? How do we can ensure that the instructions the scientist builds actually match what the system can do?

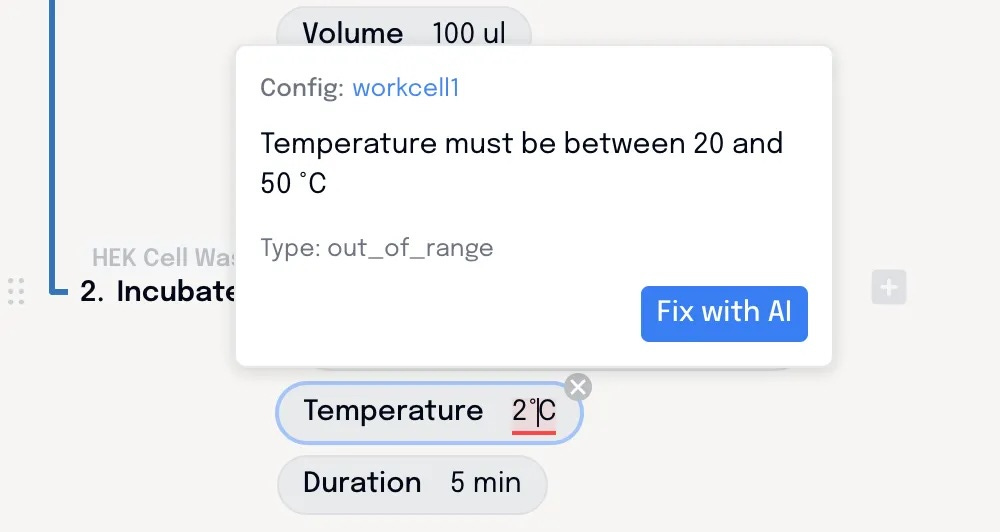

Constraints are defined by the engineer that built the automation – that could be the vendor or an internal engineer. These can then be applied to protocols in Briefly. The AI drafts protocols within these constraints – using only the steps and parameters that are allowed by the engineer. The scientist can tweak, but only inside these guardrails, ensuring that the steps they use have been tested and validated.

If a five minute incubation causes a little too much cell dissociation, they can simply tweak that parameter down. But if they want to chill their sample and their on-deck incubator doesn’t cool, then the tool will let them know. All these details can be ironed out without an engineer needing to be involved.

So while an AI can’t take a paper and run it on a robot, it does offer an opportunity to chip away at the wall that exists between scientists and automation, and get those idle robots running – not just for highly defined and parameterised workflows, but for the slippery stuff that has consistently evaded automation.

If you’re interested in using Briefly as an interface to your automation – either as a vendor integrating with us, or as an end-user interested in using this to power your automation, drop us your details below and let’s chat!